Juan Ding, OD, PhD

This is a case where two rare eye conditions happen to the same patient, as if they win the lottery (of the unfortunate) twice.

I saw Mary (not her real name) in her early 50s last year. She came to me because she had seen new floaters in the left eye for 1 week. I have written about floaters previously, you can find them here, here, and here for more information.

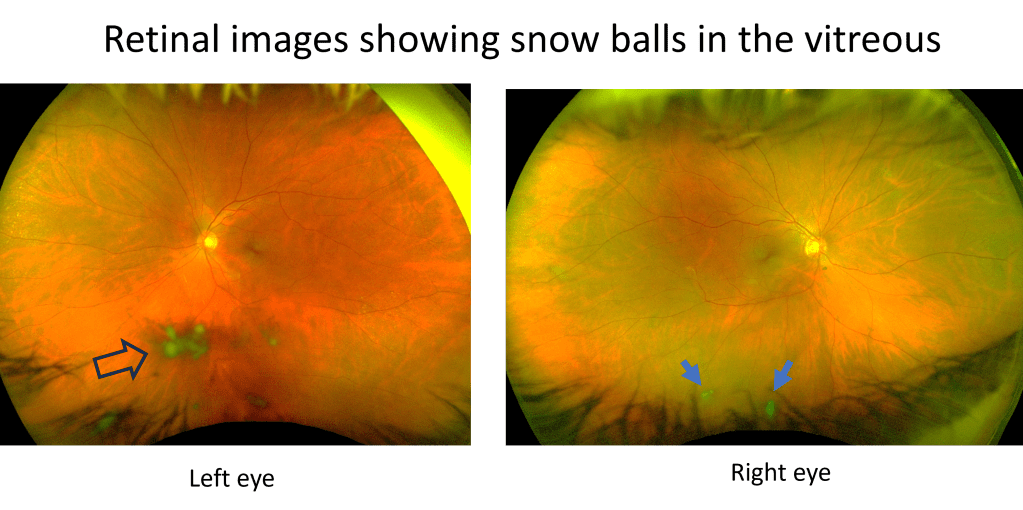

There are floaters that affect almost everyone: the regular floaters and the acute PVD (posterior vitreous detachment) floaters, and there are also weird floaters that affect only a few who win a lottery in the weird eye condition category. Mary won that lottery unfortunately. There were snow balls in her left eye, inside the jelly we call vitreous. You can see these snowballs when looking at her retina (Figure 1).

This is called vitritis, an inflammation of the vitreous (which is the jelly inside the eyeball). When vitritis happens alone without inflammation in other parts of the eye, it is called intermediate uveitis. The most common symptom of intermediate uveitis is floaters. The snow balls are actually the immune cells accumulating inside the vitreous. It is critical we find out why inflammation happens there, because some of them can have serious health consequences to a patient’s vision and even life.

Common causes can be infections such as tuberculosis, leprosy, Lyme’s disease, syphilis, toxocariasis; autoimmune diseases such as sarcoidosis, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, Sjogren’s disease, tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome; and cancer such as lymphoma.

I referred Mary to a uveitis specialist, who did an extensive workup and did not find a cause for her intermediate uveitis. This happens more often than not in medicine. But at least the infectious causes had been ruled out, so immune suppression treatment can be started; if the cause is an infection, then immune suppression will make things worse. She was started on oral steroids to treat the presumed autoimmune cause (though unclear what it is. She saw a rheumatologist but no diagnosis was found). She got better, but vitritis returned after the steroid taper. At that time they also found increased transaminase indicating a liver problem so no more oral steroids were given. She saw a GI specialist, who did not find a cause of increased transaminase level, and a few months later the level got better on its own.

Given the potential liver issue, no oral steroids, but eye drop steroids were given to her to treat the vitritis. She got better for sometime, but then her eye pressure spiked as a side effect of the steroid eye drops, which had to be discontinued. Meanwhile vitritis started in her right eye as well (Figure 1).

Next step of treatment would be a systemic agent that does not cause liver damage. The uveitis specialist was able to get insurance to pay for Humira (Adalimumab), and with this medication, her vitritis and floaters finally got better in both eyes up until now. This medication blocks the activity of TNF, a molecule used by our body’s immune system to create inflammation. Less TNF means less inflammation in the eyes, and it has been working for her.

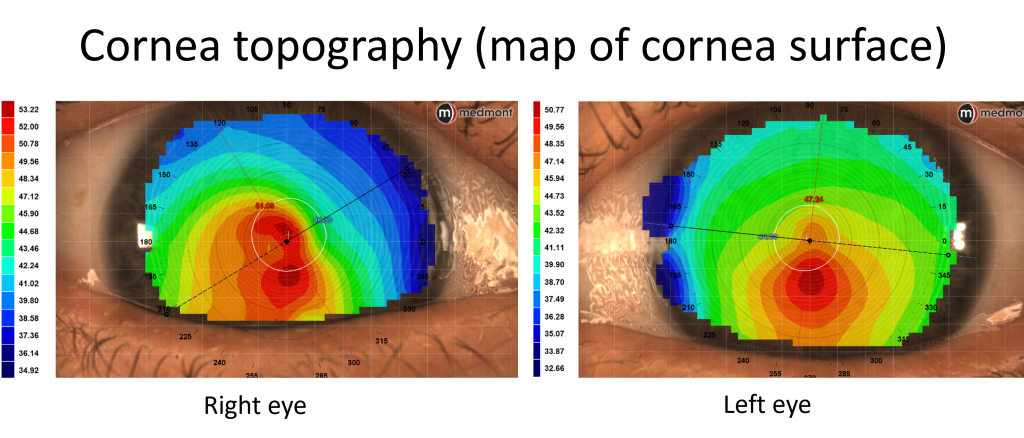

She came back to me again for new glasses now. A year ago when she first came to see me, she was wearing her new glasses of just 3 months. She had myopia and astigmatism in both eyes, more in the right eye. In that visit 1 year ago I actually found more astigmatism in the right eye and gave her an updated script. It was a little unusual to have a change in just 3 months, but she had other things to worry about for her eyes (the vitritis), so this was not pursued. Now her vision was blurry, and the right eye had a further increase in astigmatism. This is not normal. So I ordered a corneal topography, and sure enough, she actually has keratoconus in both eyes (Figure 2).

Keratoconus is not a common eye condition, and you can read about it in my previous articles here and here. It often shows up among young people, as the disease tends to progress at a young age. For her to progress and get a diagnosis at 53, that was unusual. Talking about coincidences, I happened to have another 52 year old female patient on that same day whom I diagnosed keratoconus 6 months ago. She also started having vision problems only in the recent couple of years. Life sometimes cannot be explained by just random events, or we humans are just too good at picking up anomalies.

Anyway, the prevalence of intermediate uveitis is very low, about 6 out of 100,000 people. The prevalence of keratoconus is higher, about 5%, but still not a common condition. For her to have both, it is a chance of 3 out of 1 million. Winning two lotteries!

I would not want her luck. Getting either one of these conditions is a frustrating journey in gaining vision back. She is frequently in doctor’s offices, taking eye drops and medications probably life-long if she’s lucky enough to have the eye inflammation under control, may need eye surgeries and special contact lenses if vision continues to worsen with keratoconus.

After the new measurement of her eye powers, I gave her a new prescription. She was happy and said, ‘I haven’t had new glasses for over a year, now I’m ready to get new ones and see better.’ In fact, she sounded more positive than many of my healthy patients whose only problem was needing glasses. Happiness is a state of mind, regardless of the conditions that you may have physically.

References

[1] https://eyewiki.aao.org/Intermediate_Uveitis

[2] Jacinto Santodomingo-Rubido, et al, Keratoconus: An updated review, Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, Volume 45, Issue 3, 2022, 101559, ISSN 1367-0484, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2021.101559. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1367048421002058)