Juan Ding, OD, PhD

When people think of inherited eye diseases, they usually imagine problems that show up in babies or childhood, with both eyes blind. But what if I told you the same rare eye condition can show up in kids as well as the elderly — and affecting two eyes differently?

Recently, I saw two patients who were diagnosed with a condition called Best vitelliform macular dystrophy, more commonly known as Best disease. Despite the name, it’s not exactly “the best” news to receive — though, thankfully, it tends to progress slowly and isn’t typically associated with total blindness.

Let’s start with the little girl. This is a sweet 6-year-old girl who failed school vision screening and referred to our clinic. She reports that she sees everything well, but parents note that she stays close to the TV to watch. After a detailed eye exam and specialized imaging, I diagnosed her with Best disease. She was otherwise completely healthy, with no complaints — though her vision is 20/60 in both eyes.

Interestingly, even though both eyes are not seeing well, they do show very different appearances in photos. Below is the color photo and cross-sectional view of her retina (Figure 1). Her right eye is at the ‘egg yolk’ stage, while the left eye has already progressed to the late, or advanced stage of macular atrophy. My heart goes out to the family. She is so young, and yet already at the late stage of this disease. Fortunately her vision is not too bad. And that is a common feature of this condition, that vision is typically only moderately impaired even in the late stage.

Figure 1. Photos of retina in a 6 year old girl with Best disease. The two columns represent right and left eye as labeled. A, color photo of the retina with subtle changes in macular appearance. B, autofluorescent black and white photo of the macula area. C, OCT cross-section photo of the macula in both eyes. Yellow arrow points to the ‘egg yolk’ in the macula of the right eye; white arrow points to a thin and atrophied macula in the left eye.

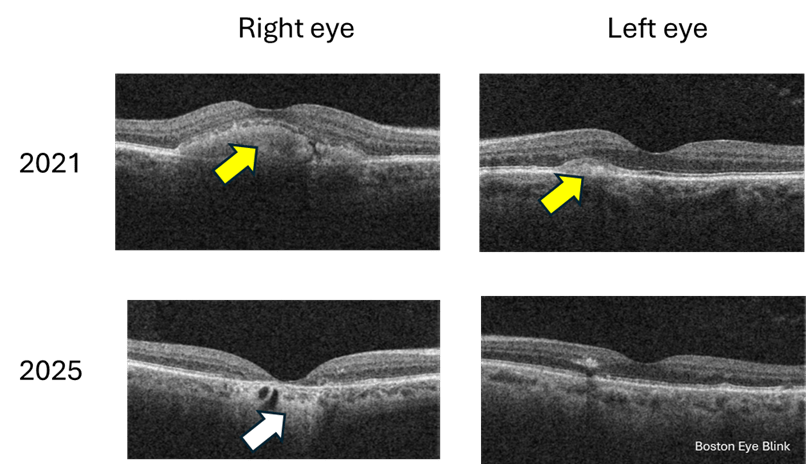

Then came the man in his sixties a week later. The two patients are not related. Just a coincidence that I would see two cases of a rare eye condition in the span of a week in a primary care setting. He started noticing blurry vision in the right eye when he was 50. He came to see us in 2021 but then lost to follow up. It gradually got worse, and now his right eye sees 20/40. His left eye sees 20/20 and no change over the years. Again, imaging confirmed the diagnosis. What is interesting is that you can see that over the 4 years, the right eye has progressed from the ‘egg yolk’ stage to ‘atrophy’ stage; while the left eye has little progression with still early or small ‘egg yolk’.

Figure 2. Cross-section macular photo of a 60 year old man in 2021 and 2025. Yellow arrow points to the ‘egg yolk’; white arrow points to atrophied retina.

So what exactly is Best disease?

This condition is so named not because it’s the best disease a person can have, it’s named after Dr Franz Best, a German ophthalmologist, who described the first pedigree in 1905.

Best disease is a rare genetic condition that affects the macula, the central part of the retina responsible for sharp, detailed vision. It’s caused by mutations in a gene called BEST1 [1], which affects a layer of cells beneath the retina called the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). This layer helps keep the retina healthy and functioning properly. The prevalence is about 1 in 20,000 [2], so very rare.

The condition often runs in families and usually appears in childhood or adolescence, though some people — like my older patient — might not show symptoms until later in life. However, the adult onset Best disease may also be caused by mutations in genes other than BEST1 [1]. The onset of age ranges from 3-15 years of age [3]. It typically affects both eyes, though in some cases the two eyes show different rate of progression, which happens to be in both my patients.

Best disease is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, meaning if there is one faulty gene, the disease will manifest. Therefore if one person has the disease, some of their family members are likely to have it too. But the degree and extensiveness of the disease can be quite variable among individuals [1], sometimes even with the condition, the person may not have any symptoms.

Interestingly, for both of my patients, they report no knowledge of any family history of low vision or blindness. I highly recommend the direct relatives to have a comprehensive eye exam with retinal imaging – the most important being the fundus imaging and OCT which can show cross section of the retina tissue. This technology can show the most striking feature, the yellowish lesion in the macula that looks a bit like an egg yolk — which is why doctors often call it a “vitelliform lesion.” You can see these lesions in the girl and the man in Figures 1 and 2 above. Over time, this lesion can change shape, break up, or leak fluid, leading to vision changes. In late stages, the macula becomes atrophied, meaning the tissue dies and thins out.

Can it be treated?

There’s no cure for Best disease, but the good news is that many people maintain useful vision throughout their lives. Regular monitoring is key to catching any complications early, especially if fluid builds up or if abnormal blood vessels form — in which case treatment might involve medications or laser therapy.

Recently, people are attempting gene therapy of this condition in dog models [4]. Hopefully gene therapy becomes available in the future in humans affected by this condition.

Why does this matter?

These two patients — so different in age and life stage — are a reminder that eye disease doesn’t always follow predictable rules. For example, Best disease usually affects both eyes, but these two patients both show remarkable asymmetry in stages of the disease. Best disease progresses slowly, and while it is true for the elder man, for the little girl, one eye is already at advanced stage. Given her young age, I imagine the progression has been fast.

And while it may not be “the best” diagnosis to receive, with proper care and awareness, patients can still live full, visually rich lives.

References and extended readings

[1] https://eyewiki.org/Best_Disease_and_Bestrophinopathies

[2] Tripathy K, Salini B. Best Disease. [Updated 2023 Aug 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537290/

[4] Amato A, Wongchaisuwat N, Lamborn A, Schmidt R, Everett L, Yang P, Pennesi ME. Gene therapy in bestrophinopathies: Insights from preclinical studies in preparation for clinical trials. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2023 Dec 1;37(4):287-295. doi: 10.4103/sjopt.sjopt_175_23. PMID: 38155675; PMCID: PMC10752275.