Juan Ding, OD, PhD

I saw a woman in her late 60s 3 months ago. She had moderate cataract and dry eye, and I recommended some basic treatments of dry eye and asked to see her again in 3 months to check if the dry eye responds to treatment.

So now she’s back again, her dry eye remained about the same despite doing what I told her. I now prescribed a medication eye drop to use twice daily in addition to the basic dry eye regimen.

At the end of the visit, she asked me something else. ‘My vision is blurry on the left side compared to the right side, when I am reading or looking at people’s faces. This has been going on for a month now.’

This triggered a red flag, as the way she described it, it indicated that both eyes are seeing blurry on one side vs the other, and that would be brain thing, not an eye thing.

I immediately did a confrontational visual field, which entailed asking her how many fingers I was holding up in either side of her peripheral vision. This was however inconclusive, because she was hesitant but answered correctly for both sides.

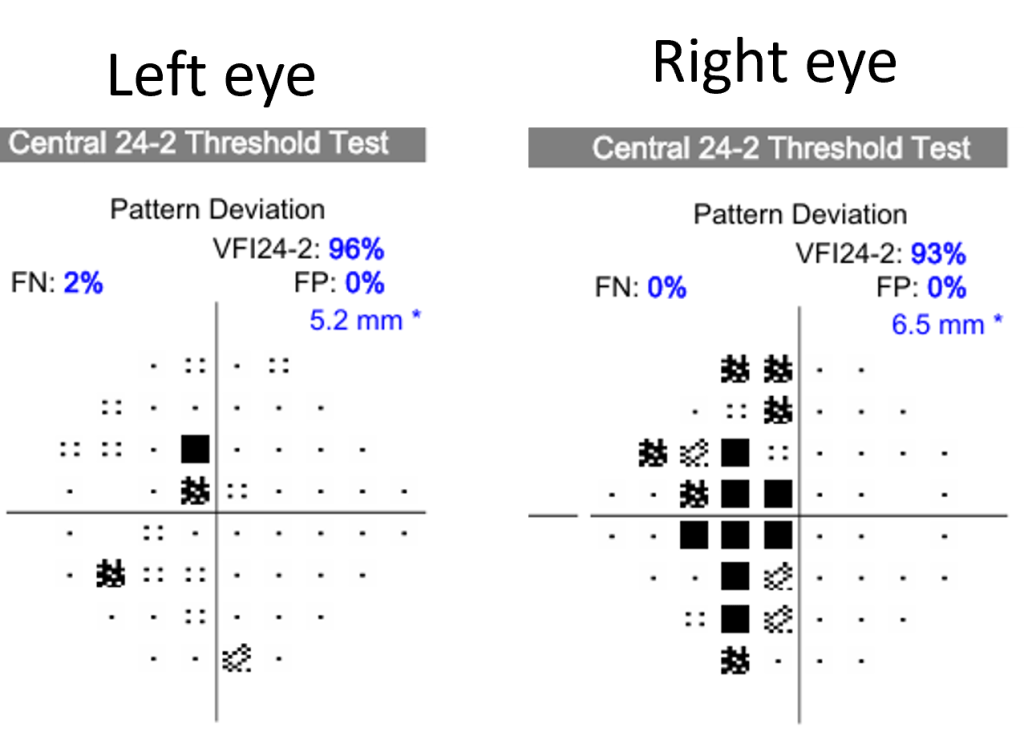

So I ordered a formal visual field testing, called Humphery Visual field test 24-2. This is a much more sensitive test than counting fingers and can quantify the sensitivity of peripheral vision in a given field of view. Fifteen minutes later, it showed results as below.

You can see that the right eye has a dark area on the left side, and the left eye also, but to a much less extent. What is unique about this visual field is that the dark area is only a relative defect, meaning she could still see fairly well, only less well compared to the right side. That is why she was able to tell the number of fingers in both right and left sides. But this also is consistent with her complaint, she’s not saying that she could not see one side of the face or a book, but just that one side was more blurry.

This could still be a hemianopsia, like I talked about in a previous article, in which the other patient had a stroke.

So immediately I needed to rule out that she had a stroke.

She denied almost all of the stroke symptoms I asked about her, including headache, double vision, numbness or weakness. She appeared well and healthy, with no acute distress. She had high blood pressure, and was taking medications for it. She did not have diabetes or high cholesterols. Further, her symptom of one-sided blurry vision had been going on for 1 month already, so in all, this was unlikely to be a stroke.

So I did not need to send her to ED, but my job was not done yet. We still needed to figure out why she was developing the symptom. So I asked her to follow up with her PCP to investigate this. I faxed her record to her PCP and asked her to call her PCP if she did not hear from her that week.

Still feeling uneasy, I kept thinking about her. The visual field was suggestive, but the left eye was so mild, and it’s actually not quite reliable, you could almost say this result should not count. And if you only have a defect in one eye, that would not be a hemianopsia. That would be an eye thing, and not a brain thing. Yet with all the reasoning, I couldn’t help feeling worried, because she was very specific, clear and accurate in describing her symptoms, which showed up exactly in the test.

Something is not right. Next day, I ordered a brain MRI with and without contrast, which initially I wanted to defer to the PCP, together with other tests.

Less than 2 weeks later, a letter with red flag arrived in my inbox. I opened it up and saw her name. Her brain MRI was out. As I scrolled down the radiology report, one glimpse of the work ‘a large mass’ was enough to give me the chills. My biggest worry turned out to be real. She had a large meningioma that compressed onto the occipital lobe, which caused her visual symptom.

Action was taken quickly. She had whole body scan and fortunately no tumor was found anywhere else in the body. A week later, she had surgery to have the tumor removed and now she’s in recovery.

Most meningiomas do not spread to other parts of the body, as is her case (at least so far as we know), and successful surgery can lead to a good prognosis.

I hope she gets well soon, and hope to see her doing better with her vision in 2 months at her scheduled eye exam visit.

In addition to stroke, brain tumor is also a common cause of hemianopsia. In contrast to a stroke, a tumor may cause symptoms gradually and slowly, as the growth of the tumor can be a process, rather than in a stroke where a blood supply is suddenly cut off. Therefore symptoms that are more slow in onset and sometimes even vague should raise suspicion of a tumor.

Small clues may unravel large tumors, be on the alert for small clues.