Juan Ding, OD, PhD

I recently saw a gentleman in his 70s due to double vision. He started seeing double vision 3 weeks ago at the airport. When he looked out of the window he saw two planes taking off though he knew there was only one. When he covered either eye, the double vision went away. But with both eyes open, he was seeing double images. But this was not happening all the time, only intermittently, and more when he’s tired.

He reported that similar double vision happened 15 years ago briefly, after he took some cold medicine, and it resolved on its own after he discontinued the medicine.

He did not recall any head or eye injuries. He did not have any other neurological symptoms. He felt well and did walking or cycling regularly. There was no history or family history of autoimmune conditions. He did have type 2 diabetes which was well managed. He had no history of heart disease or cancer. As for new medications, he remembered having covid-19 booster vaccine a month prior to the onset of double vision.

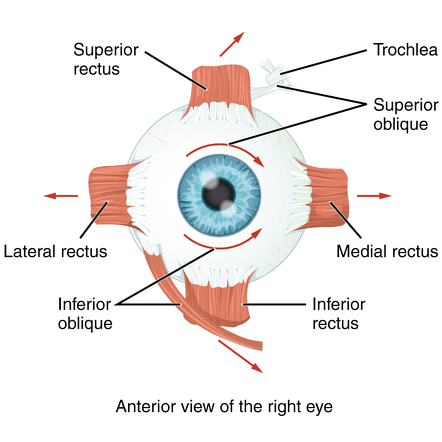

His history clearly indicated that his double vision was because the two eyes were not working together as they should. Many causes can lead to this. Each of our two eyes are controlled by 6 small muscles surrounding the eye (Figure 1). The two sets of corresponding muscles need to work in synchrony in order for the two eyes to look at the same object. If they don’t work in sync, double vision ensues. The first step is to find out which of the eye muscles are at fault. Because these muscles are in turn controlled by different nerves. Finding out which ones do not work will indicate which nerves are not working, and help to find out what is causing the nerve or muscle dysfunction.

Both of his eyes were able to move in all directions. I then did a careful measurement of his eye alignment, and found that he had a very small vertical misalignment between the two eyes. It was invisible by naked eyes, and only detected by doing an alternate cover test, in which each eye is alternately covered to show a deviation pattern. The result was that the left eye appeared to be slightly higher than the right eye. But it was such a small number and it appeared to be consistent in all directions where he looked. This is what we call a comitant deviation as it shows no difference depending on where a person looks toward. Having a comitant deviation usually indicates the problem has been chronic or benign. Further, the issue is not pinpointed to any specific eye muscle. Rather, multiple muscles may be involved.

The next step is to check if there are any other associated abnormalities. Pupil size differences or reactions to light often are altered in certain nerve disorders. He had normal pupils. Eyelid positions were also often abnormal with some of the nerve problems. His eyelids were symmetrical and both slightly loose and droopy normal at his age.

His vision in each eye was stable, and he just saw another eye provider for a dilated eye exam not long ago with no remarkable pathologies.

So I thought this was a decompensated phoria issue. This means that the person has a slight misalignment between the two eyes and usually well compensated; in certain situations, for example, when tired, stressed, or aged, the compensation reduces and they start seeing double images.

While he was in my office, he was actually not seeing double, indicating a good compensation. Still, since he did frequently see double for several weeks, I offered to try some prism to alleviate the problem. Prism changes the direction of light, and can therefore allow two eyes see the same image if light direction is altered just matching the misalignment. He felt seeing things more clear and comfortable with 1 unit of prism. Interestingly, he felt comfortable and clear with up to 5 units of prism before he complained of seeing double at 6 units. This type of a relatively large range of fusion often indicates a congenital misalignment. The most common being congenital cranial nerve 4 palsy. However, this did not appear to be what he had, as he had no head tilt now or in his driver’s license photo, and the comitancy of the misalignment that we discussed earlier also did not fit.

This was not a typical case. It was not likely from a brain etiology, but some of the mimickers that can cause double vision should be ruled out. So I ordered blood tests for myasthenia gravis and thyroid eye disease. I prescribed prism glasses and asked him to follow up in a few weeks.

To my surprise, a few days later, his blood test was positive for myasthenia gravis (MG), an autoimmune condition that weakens the communication between nerves and the muscles they control. I immediately referred him to a neurologist, the speciality that diagnoses and treats this condition.

The neurologist concluded that he had the ocular MG, which affects only eye muscles. However, with time many patients with ocular MG may convert to generalized MG, with muscle weakness affecting other organs of the body. The most serious would be the muscles for swallowing and breathing, as they may develop difficulty breathing, which can be life-threatening. Further, a subset of MG patients also have a tumor in their chest, called a thymoma, and 30% of these tumors are malignant. So my patient is going to have a chest CT very soon.

I saw him again for follow up and he reported seeing well with the new glasses and did not have double vision any more. With ocular MG, the double vision could change pattern over time so we would monitor this regularly. Given that he had no other symptoms, no additional treatment was necessary at this time and he was also being monitored by the neurologist regularly.

My patient does not require additional treatment besides prism at the moment, but if his symptoms change, additional treatment may be necessary. For example, medications such as pyridostigmine, oral steroids, immunosuppressive agents, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG), and biologics. When difficulty breathing develops, patients should go to emergency room to have prompt IVIG treatment as it can be life-threatening.

MG can present in the eyes first. In fact, almost 50% of MG present as ocular MG [1]. But up to 60% will eventually convert into generalized MG [1]. One classical feature of ocular MG is the incomitancy of double vision, which we discussed above. This means that double vision or the misalignment of the two eyes is different depending on which direction the person looks at. As you recall, my patient had comitant deviation, which was why it surprised me that he tested positive for MG in the blood test. However, it’s a relief to find in literature that 25% of ocular MG were reported having comitance or change of comitance to incomitance or vice versa [1]. Further, another classical presentation of ocular MG is ptosis, or droopy eyelid, which my patient also did not have. MG diagnosis is often delayed in cases where there is only double vision and not ptosis.

Another interesting observation is that there were multiple reports of new onset MG shortly after covid-19 infection or vaccination [1]. However, a causal relationship was not well established. I did not think twice about his covid booster, but seeing that this is observed in the scientific community, I will probably ask about covid infection of vaccination in future suspected MG patients.

Lesson learned is that even an atypical case of double vision could be MG. Having no ptosis does not mean it cannot be MG. Being comitant in double vision does not mean it’s not MG. Don’t ever forget to rule this condition out.

For more information, please refer to this excellent review article [1]. Direct references and much more information about ocular MG can be found in there.

Review article cited:

[1] Behbehani R. Ocular Myasthenia Gravis: A Current Overview. Eye Brain. 2023 Feb 5;15:1-13. doi: 10.2147/EB.S389629. PMID: 36778719; PMCID: PMC9911903.